- Home

- Chris Van Etten

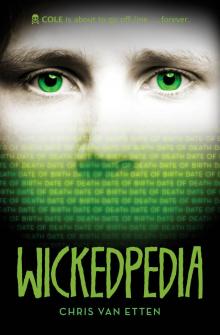

Wickedpedia Page 13

Wickedpedia Read online

Page 13

Cole heard the words. They were definitely English. But he couldn’t make heads or tails of them. “But you said I’m going to be fine.”

Gavin put on his “patient” voice, which was less “patient” than it was “superior.” “Yeah, because he went splat underneath you and you went all bouncy castle right off his muscle and meat. Guess all that soccer was good for something, huh? He saved your bacon.”

“But he’s going to be okay, right?”

“I guess. As long as the guys in cellblock D don’t use him as a go-kart. Josh’s gonna be rolling for the rest of his life.”

There was a kid at school, Adam somebody, who used a wheelchair. They didn’t share any classes but Cole knew from Gavin’s complaining that he got let out a few minutes early every period to head off to his next class, a luxury Gavin sorely desired because “Add up all those minutes and it amounts to an extra nap every week, two if you like ’em short.” Cole felt as though every time he saw Adam it was at the opposite end of a hallway, and he was just turning a corner, wheeling out of sight. He wondered what it would be like to live life as a mirage, to be seen and not seen at the same time.

Gavin saw Cole’s conscience wrestling Josh’s injury on his face. “Don’t feel bad about it. So what if he never walks again, never kicks another ball? He got what he deserved. If it wasn’t clear before, it is now. He killed people. And not just any people. He killed Winnie.” Cole put his hands over his eyes. Hearing Gavin say it was different than saying it himself. Cole’s chest began to jerk and spasm. Gavin pretended not to notice. “But now he’s screwed, and you’re the one who screwed him. You’re a hero.”

Cole looked up at Gavin, his eyes red. “I am?” he snarled.

“It’s all over the news! Spring Showers has been camped out in the parking lot ever since you got here, competing with a slew of other reporters to bag you for an exclusive. You’ll be glad to know I selflessly allowed her to bag me instead. For an interview, that is.”

“No,” Cole burbled. “I can’t. I can’t see reporters.” His head was oppressed by the image of Winnie, dead at her desk, slumped over like she’d been deboned. “They’ll ask me things. I can’t talk about it. I can’t even think about it.”

“You don’t have to talk to the reporters if you don’t want to.” Now Gavin’s voice was mild, a chain-restaurant salsa. “But you are gonna have to talk to the police. Not right now. But soon. When you’re done and over your rainbow. They’re gonna want to hear what happened straight from your mouth. So they can put this whole thing to rest. You can swing that, right? For Winnie?”

Cole doubted he could. But he knew he had to.

Gavin looked behind him, then back at Cole. His voice was lower now. “And when you do talk to them, do us both a favor and remember what we talked about last time, okay? Leave out the whole Wikipedia revenge-plot aspect. No sense confusing the ‘Valedictorian Catches Serial Killer’ narrative with behavior some might call bush-league, right?”

“But I’m not valedictorian!”

Gavin cocked his head. “I think we both know you will be now. Congratulations in advance.” He got up to go. “Time to get ready for my close-up. Spring is expecting an update.”

“Gavin?”

“Yes, dear?”

“Are you sure I’m not dead?”

“Sure I’m sure. If you were dead, I’d be dead. And I’m kicking. So, so are you.” He walked out before he could hear Cole add something out loud, for his own ears.

“For now.”

Gavin hadn’t seen what happened in Winnie’s room, nor what was on her computer when Cole clicked the link for his name. Soupy as his thoughts were, he managed to piece together what he’d read on the screen.

Cole Redeker

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

* * *

Cole Redeker is an American high school student of little significance. He thought he was smart. He thought he was talented. He thought he was entitled to a bright future. He was wrong. He died stewing in his own juices.

There on the screen was Cole’s life. And the date of his death.

December 12.

One week from his fall.

This weekend.

When his doctors agreed to let Cole go home, it was days later — the date fixed for his expiration. His stay in the hospital was marked by an endless march of Mylar balloons and stuffed animals gifted from newly admiring SHS females who’d never, not once, even sneered his way; Spring Showers, intrepid inept reporter was twice caught sneaking into his room, once in scrubs and a face mask and again posing as the hospital librarian; the mayor’s announcement that the street leading to the school would be renamed “Redeker Road”; and Winnie’s burial.

Cole would not attend.

His parents and doctors refused to consider discharging him in time for the service. “You sustained two head injuries in one day,” said his neurologist, waving Cole’s brain scan, a mosaic of inkblots.

He was secretly grateful for their veto. It was a scuzzy feeling, but surely it was better than purging his grief and guilt all over a church full of Winnie’s friends and family. Reading her obituary was all it took to rumble up great, bone-seizing sobs. Cole was certain if he didn’t spontaneously combust just setting foot inside the church, he’d disintegrate as soon he saw her casket. By his logic, he was right to stay away. That became obvious when the police finally came for him.

“I know you’re going through a hard time right now so we’ll take this nice and easy,” Detective Simms told Cole, though he got the feeling it was said for the benefit of his parents and the lawyer they’d hired to represent his interests, all of them crammed into his hospital room. On the other side of the curtain came the hollering snore of his roommate, Mrs. Osborn, a septuagenarian with operable sleep apnea. Cole was glad to know his misery wasn’t keeping her up. “I just need to hear your account of what happened,” Simms said.

“What happened to the other detective?” Cole asked.

“What other detective?”

“I never got his name,” Cole said. “The one who talked to me at school … after my teacher got killed.”

“You mean Morris,” said Simms. “He needed a break, and we decided to go in another direction with this investigation.”

Cole wondered whether a new detective wearing a coffee-stained tie was really the new direction the police should be taking. “Don’t you already know what happened?” he asked. “Gavin said it was all over the news days ago.”

“I’m sorry, Gavin?” Simms asked, stooped over Cole with a notepad and pen in hand, his bald spot glaring like a spotlight. “Who’s Gavin?”

The question was not asked of her, but Cole’s mother was raring to answer it anyway. “Just the neighborhood hoodlum.”

“And my best friend,” said Cole. “We were together at school when we found Drick, Mr. Drick, I mean,” he corrected.

“And he told you what?”

“That the story had already hit the news. Why, what’s wrong with that?”

“Nothing.” Scribble. “Just getting my facts straight. Tell me about the night you went over to Winnie’s.”

“What do you want to know?”

“Why were you there?”

“She invited me to come.”

“Did that seem strange to you?”

“Why would it? We were friends. Sort of.”

“Sort of friends?”

“We weren’t very close before she …” Cole swallowed and held his breath, then began again. “Before Josh killed her.”

Simms persisted. “But you were closer at one time before?”

“She was my girlfriend. But we weren’t so close anymore because she broke up with me to go out with someone else.”

“And that someone else would be Josh Truffle?”

“Yes. Him.”

“And you and Josh used to be friends, is that right?”

“Who told you that? Josh?”

“Was I tol

d wrong?” Simms breezed, as if they were all friends here.

“We played soccer together when we were kids. We never got much closer than that.”

“Sounds like you don’t like him.”

“What’s to like?”

“Easy, Cole,” warned his father.

“No, Dad. I used to feel bad about Josh’s troubles and I suppose I should feel even worse now that he can’t walk. But now I can see him for what he really is and I won’t pretend otherwise.”

“What is he?” asked Simms.

“An entitled jerk. The administration cushioned his grades to keep him from getting kicked off the soccer team. He made an art of cheating and plagiarizing, making fools of everyone else who followed the rules, and the minute he got caught he acted like he deserved to get a special dispensation from the consequences! He bullied Winnie into staying with him when she knew better, but when she finally got her back up and cut him loose, he killed her for it! After he’d probably already killed his best friend and my teacher!”

“Probably? You don’t sound so sure.”

In fact, part of Cole wasn’t so sure. Hadn’t Josh accused him of killing Winnie when he came into her room?

“What does it matter whether or not I’m sure?! I’m not a detective!”

“Cole,” his mother said, trying to interrupt with all the oomph of a cobweb.

“But instead of detecting how Josh came to choke Winnie to death, you’d rather take me on a walk down memory lane to when we were eight years old and he stole my Gatorade at soccer camp!”

Cole’s lawyer sniffed and called a halt to the interview. “My client is distraught.”

“Just a few more questions, counselor? You can do a few more questions, right, Cole? When you entered the house, did you notice anything out of the ordinary? Anything out of place?”

“No. But I hadn’t been inside since before we’d broken up. How would I know if something was weird?”

“Go on. You went up the stairs.”

“The light in her room was on. I went in. She was at her desk. Something was wrong. Her hair. It was around her neck.”

Squeezing.

Constricting.

Drowning her insides with dead air.

Was she waiting for him? Did she think he’d come for her?

Did she know who killed her?

Did she think it was him?

Did she die thinking he’d murdered her?

“She was strangled with her own hair. She was dead.”

Cole heard a sound like the opening of a can of soda and looked toward it. His father’s arm was around his mother. They were shedding tears, their faces contorted. Their breathing labored. If Cole hadn’t already seen Winnie’s body, his parents’ woe would have been the worst thing ever.

Simms cleared his throat and looked up from his notes. “When did Josh arrive?”

“After I —”

He stopped.

“After you what?”

After Cole saw Winnie’s death chronicled and his own death foretold on Wikipedia pages.

After he saw the Wikipedia pages that could incriminate him.

Gavin was right. Telling the truth might only make it harder to punish Josh.

And Josh needed to be punished.

“He showed up after I vomited.” It was the truth. Some of it, at least. “I saw Winnie and got sick. Then Josh came. He said, ‘You killed her.’ Then he came at me and we went through the window. The next thing I knew I was here. I don’t know what happened in between.”

“It was just a few minutes before the ambulance and uniforms arrived,” said Simms. “A Good Samaritan saw you fall and called 9-1-1 right away.”

“We’d like to thank that person,” Cole’s mother said.

“So would I,” said Simms. “But whoever it was didn’t stick around, and the phone company says the call was made from a burner.” Cole’s parents didn’t know what that meant. “A prepaid, disposable cell phone. No name attached to it.”

Cole’s lawyer cleared his throat. Cole had forgotten he was there and wondered if he’d dozed off. “Is that all, detective?”

Cole needed it to be all, before his chest caved in and sucked him into himself, leaving just his hospital ID bracelet. Simms drew a finger across his lip.

“Last thing, I promise. Why do you think Josh said what he did? Why do you think he told you that you killed her?”

The detective was thinking the same thing Cole was. “Maybe he blamed me for making him kill her. Maybe he’s crazy. I don’t know why he said it. All I know is he killed her.”

“How do you know? You didn’t actually see him do it.”

“Because I just do. I told you, the front door was open when I got there. Someone had already gone inside and killed her. It was Josh.”

“The front door was open, sure,” Simms said. “But the back door was locked. Did you know that, Cole?”

Simms was getting at something. Cole didn’t know what it was, but he knew it wasn’t good.

“See, Winnie knew we were looking for Josh. She knew we strongly suspected him of killing his friend and his teacher. Winnie’s parents knew this, too. They told me they were very careful to lock the doors after they left for work the day she died. Her father called her from work after she got home from school to make sure she’d locked the front door again behind her. She told him she had. So it leaves me with a problem. Why was the back door locked, but not the front door?”

Cole yearned for a mute button. “I don’t know.”

“Here’s one theory on how that came to be,” Simms said. “Winnie got home from school, let herself in, and locked the door behind her. A while later someone rings the doorbell. She looks out the window and sees that her caller is someone she knows. Someone she doesn’t believe is dangerous. Someone she trusts. Maybe even someone she’s expecting. So she unlocks the door and lets them in.”

If Cole’s mother had been wearing pearls, she would have clutched them. “Just what are you trying to say, Detective Simms?”

Simms licked his lips.

“I’m just saying it’s interesting.”

He’d shucked the look of the shambling, nice-and-easy detective just out to fill in some blanks, and revealed a more authentic expression. He leered at Cole, all teeth. Cole knew this look. He saw it every time someone caught the aroma of his latest confectionary experiment. The detective was famished. And Cole was his meal.

“What he’s trying to say, Mrs. Redeker,” came Mrs. Osborn’s squeak from beyond the curtain, “is that Josh isn’t his only suspect.” Her snoring had stopped long ago, just as Cole’s troubles were taking a turn for the worse.

Cole was released the next day. Per hospital policy, he climbed into a wheelchair and allowed a nurse to trundle him down to the lobby, where his mother waited. His father looped around the hospital grounds in the car until they were ready to make a run for it, weaving through the gauntlet of reporters gathered outside hoping for a quote from Springfield’s hero, “Winnie’s Avenger.” What they didn’t know — what no one knew, thanks to the tight lid the police were keeping on the investigation — was that the police regarded him as a potential killer, right along with Josh. But during the course of the interview, Detective Simms had hardly mentioned Drick or Scott. Did the police think Josh killed them both? Had they still not picked up on the Wikipedia pages? Or were they waiting to spring more accusations on Cole during another surprise interrogation? Whom were they after? Why hadn’t Josh just confessed and finally put an end to this?

“Here he comes,” Cole’s mother said, spotting his father’s Camry darting up the driveway to the hospital entrance.

Cole got up and went back the way he came. “Tell him to make another pass, Mom. I forgot something upstairs.”

“Cole, I want to get out of here.”

“Me too. Couple of minutes, that’s all.”

The elevator doors closed behind him, cutting off her clucking. He had a feeling he’d need mo

re than a few minutes. But he had a visit to make, and he couldn’t leave the hospital until it was concluded.

Admittance to the ICU was controlled by nurses stationed opposite clear Plexiglas doors that locked and unlocked at their discretion. Cole didn’t know if visitors were limited to close family, but he wouldn’t take any chances. When the nurse on duty looked up and released the locks, he had his story ready.

“I’m here to see my grandmother.”

“Name?”

“Uh, Osborn.” The splintery old lady had suffered complications during her operation. “Gramma Osborn.” Cole had never asked her for her first name, and if she’d volunteered it, he’d tuned her out.

“I can see the resemblance,” the nurse warbled. “Delia’s a sweetheart. You’re a good boy to come visit her.” The nurse pointed to a corridor leading away from reception. “Down the hall, take a left. First room on the right. And don’t forget to sanitize those hands.”

Cole prowled by stores of supplies, drawers of bandages and syringes, unattached IVs, and empty gurneys idling outside dimly lit rooms. Inside those rooms, patients seesawed between life and death. Tiny sounds crept into the corridor, the whooshes and blips of ventilators and cardiac monitors keeping time to the coo of a loved one’s prayers. Cole ducked a glance into each room, on the hunt.

A police officer dozed on a stool by a door at the end of the hall, his hand loose around an empty coffee cup. Cole knew the patient inside wasn’t going anywhere. Not in his condition. There was only one reason the cop had any business sitting there.

He was there to protect the patient from someone who might do him harm.

Someone like Cole.

The cop’s head bowed and jerked twice, as if in response to some dreamed question. Cole retreated into a pantry and put on a fresh pot of coffee. The scent of roasted Arabica slithered down the hall and curled around the cop. He awoke, took a quick look back inside the room, and went off in search of caffeine. Cole let himself into the room the cop had left behind, closed the door behind him, and drew the blinds.

A lamp on a side table cast a warm glow over the room. Whirring, hissing machines kept solemn council around a bed. In it lay Josh. Purple bruises rampaged across his skin, where it wasn’t already wrapped in gauze or casts. A skullcap of white bandages was fitted to his head, immobilized by a neck brace. Cole could not look directly at his face, which was less a face than a collection of human features cut into puzzle pieces, mixed with other puzzles, never to properly fit again. Josh was nearly turned inside out, his nose a crater, his eyes so swollen shut they looked swallowed whole. An erector set of metal rods kept order over his broken bones.

Wickedpedia

Wickedpedia